This weekend I volunteered at an event called the Youth Excellence Recognition Luncheon, organized every year by the Vietnamese Culture and Science Association (VCSA), to honor Houston-area Valedictorians and Salutatorians of Vietnamese descent. I’m no stranger to the event. I’ve been volunteering since high school, maybe as early as 2008, and I had the privilege of being an honoree in 2010. Over the years, I’ve come back again and again to help, including as Co-Chair in 2011 and this year to sing the U.S. national anthem. I’ve always known this was a great program, but for some reason, this time, I felt the full impact of this program, now celebrating its 22nd year, and the important role that the Vietnamese-American community has in our lives.

I remember my first impressions of VCSA, even if the exact events have long since faded from my mind. It was summertime, either right before I entered high school or shortly after. I was used to lazing around at home, perhaps reading or swimming. Concerned that I wasn’t being productive, my mother strongly suggested I come with my sisters to weekly VCSA meetings. Grumbling, I let myself be dragged along to a tiny center situated on the corner of a parking lot on Bellaire Boulevard. My sisters were ten and eight years older than me—probably in college at the time—and I remember feeling dwarfed by all of these older volunteers. They looked so put together and adult. I was just a kid. I didn’t say a peep. My sisters introduced me to a friend or two, who promised to take care of me on their team for a volunteer event called TOPS (Tobacco Obesity Prevention Summit), a one-day event educating children ages 5-16 on the health effects of tobacco and obesity.

My first TOPS passed in a blur. I was young enough to be a participant, but since I entered as a volunteer, I continued volunteering in the years after. I gradually embraced interacting with kids ages 7-9, my sweet spot, and drew the t-shirt designs for a couple of years. It must have been fun enough that I thought about volunteering for other VCSA events during the summer. Their other major event was VVDV, short for Vẻ Vang Dân Việt, or the Youth Excellence Recognition Luncheon. I was definitely too young for that my first year and had to wait until I was a high school sophomore in 2008 to begin helping out. Since I hadn’t even graduated and this event was geared towards honoring high school students, there wasn’t much that I could do except one thing—sing the U.S. national anthem. Most Vietnamese parents enrolled their kids in piano or violin or focused on academics. I was the only one studying voice (and piano), which gave me this unique opportunity. I was used to performing at recitals and competitions, so I didn’t think much of it at the time, but looking back, it’s quite an honor getting to sing at an event with 500+ attendees and numerous important figures, ranging from school superintendents to senator representatives.

As I watched these eighteen-year-old honorees walk across the stage in their caps and gowns, I couldn’t wait for my turn to be a VVDV honoree. All of my sisters had their introduction to VCSA through this very program. Though I wanted the same, I also felt anxious at the possibility that I wouldn’t do well enough to earn the title of either Valedictorian or Salutatorian. During senior year, I struggled with Calculus and Dance, the two classes in danger of receiving a B. With the help of my boyfriend at the time, I eked out a 90 in Calculus, and by the mercifulness of my dance teacher, she gave me an A. It was happening. I was going to be honored at VVDV. And after that, I’d finally get to do more than sing as a volunteer.

My high school was one of the few that used a system of co-valedictorians and co-salutatorians, so my boyfriend and I were two of nearly thirty valedictorians that year. When the VVDV 2010 Co-Chairs reached out to me, I readily filled out their questionnaire and reserved the first Sunday in August for the event. My boyfriend, however, had never heard of it. I persuaded him to join in.

At the orientation for the VVDV 2010 honorees, I met a number of bright young people I still keep in touch with today. At least two others were attending Rice University in the fall, like me, while a number of others, like my boyfriend, were headed to the northeast. The vast majority would go to either UT Austin, A&M or U of H. Dressed in red, the color of my high school, I felt ready to take on the world.

During the orientation, the Co-Chairs administered a Vietnamese language test that measured reading and writing skills. The top three students would earn a small scholarship. Thanks to my mother’s diligent efforts, I aced the test with flying colors.

That year I was hoping the Co-Chairs would ask me to sing the national anthem again. Wouldn’t that be something, to have an honoree sing the national anthem! But that year they found someone else, and I thought that was probably for the better so that I could fully enjoy the program as a participant.

At eleven o’clock on Sunday, the Co-Chairs lined us up in two rows in the hall on the second floor of Kim Son Restaurant. When the time came, we filed into the ballroom to “Pomp and Circumstance” and enormous applause. With the speeches, it felt like graduation all over again. After a short entertainment program consisting of a fashion show and a few dances, we moved onto the honoree portion. Each honoree went on-stage to receive a trophy presented by either a board member of VCSA or an important official. I don’t remember who handed mine—I think he was a judge of sorts. Afterwards came the Rose Ceremony in which the honoree presented their parents with a single rose as thanks for their hard work and sacrifice. To be perfectly honest, I felt that this was a waste of time. How could a single rose possibly be sufficient for what our parents had done? Why did we need to present the rose on-stage family by family? Why not have us present the rose to our parents off-stage once the event was over? But this was tradition, so I didn’t question it. In a few hours, the whirlwind ended, and we dispersed to the winds.

If you did the experience of volunteering for VVDV right, this was how most people would have done it. They would be recognized as an honoree at VVDV. A year later, they would come back and serve on a team—Reception, Program, Entertainment, Technical, Security or as an MC, either Vietnamese or English. The following year they might step up and become a team lead. After that, they might step up and become Co-Chairs for the event. I knew a lot of people expected me to become Co-Chair eventually since I had volunteered for so many years. I just didn’t know which year I’d have the courage to do it. What if I didn’t get along well with the volunteer who stepped up to Co-Chair with me? I didn’t feel close enough with anyone to ask them to join me as Co-Chair.

The following summer after I was recognized, I heard that J, a childhood friend of mine and the same age as me, had stepped up to be Co-Chair for VVDV 2011. It was much too soon. I hadn’t properly served on a team yet. How could I think of being Co-Chair? But it seemed as though there was difficulty finding Co-Chairs. As the days passed, I worried that someone else would grab the position. I knew J, and I knew she would make an excellent Co-Chair no matter who shared the role with her. So I went for it.

The summer passed by in a blur. Within a month and a half, we contacted about 25 honorees, slapped together a flyer, conducted weekly meetings, promoted the event on Vietnamese radio, led the related College Workshop Panel, welcomed the honorees at the orientation, sped through the event, and before we knew it, it was done. It was the most work I had ever done, coordinating a team of about 50 volunteers for a 500+ attendee event.

In all honesty, I probably did not make a good Co-Chair. I have never felt comfortable leading a large group of people. My preferred position is to help behind the scenes. I remember being the main contact for all of the honorees, reaching out via email or Facebook to explain the event and encourage them to attend. I wrote the weekly meeting minutes and touched base with volunteers via email to ensure we were all on the same page. Even though I ranked first in the Vietnamese language contest, I’m not a fluent speaker. I gave the English Co-Chair speech while J gave the Vietnamese one, and she answered most, if not all, of the questions on the Vietnamese radio talk show. Swamped with coordinating the event, I reached out to a Vietnamese performer in San Antonio to sing the national anthem.

By that point, my sisters had long stopped volunteering for VVDV. I asked them why when it was so fun getting to meet young people—people like me, who share the same cultural heritage of being Vietnamese-American? How else would we meet people like us if not through volunteer organizations like VCSA? They said it simply wasn’t their thing. One of my sisters did help, however, by connecting me with local Vietnamese fashion designer Danny Nguyen Couture to provide áo dài for the fashion show.

I vowed that next year I would come back and take on a smaller role, team lead or a regular volunteer, maybe. No matter what, I knew I was coming back.

The summer after, I discovered that once you’ve served as Co-Chair, there’s no going down the ladder of leadership. It’s the most amount of work you will ever do, and knowing the big picture, it’s difficult to take on a smaller role. J, being out-of-state, and I helped mentor the next pair of Co-Chairs on organizing the event, essentially becoming “Program Consultants”—a role, I learned, that all previous Co-Chairs take on afterwards if they continue to volunteer. With other commitments during the summertime, I declined taking on a major role and ended up where I first began—singing the U.S. national anthem.

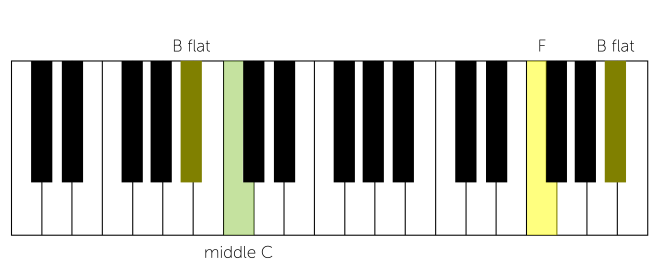

My relationship with this song has evolved over the years on its own journey of personal discovery. One reason the national anthem is so difficult for most people to sing without previous training is due to the wide range of notes. I’m no Beyonce or Mariah Carey, but through the years I’ve done my best to sing the national anthem as well as I can. Sung in the original key of B♭ Major, the lowest note is a B♭ below middle C and the highest note is an F about an octave and a half above middle C. At the highest point of the song—“o’er the land of the free”—some singers sing just the F. If they’re a bit more ambitious, then they first hit the F before soaring up to a B♭, but that’s pretty tough to do.

Here’s an interesting thing I learned about singing as a soprano from my voice teacher. The breaking point from when you switch from a lower voice to a higher voice is between F and F# above middle C. That means if a song is mostly written at or above F#, it fits the vocal range of a soprano than a song mostly written at or below F. “The Star Spangled Banner” originally starts on an F, a less than ideal note, and in high school I had a lot of difficulty hitting the lower notes like B♭. Since I was the only one singing the national anthem acappella, I decided to transpose the song up to start on an F#. That would give me an easier starting point as well as raise the lowest note by a half step.

The first year or so, I stayed on the conservative side with just the high F# for “free,” no reason to try anything crazy in front of 500 people. As I continued to sing in college as part of an acappella group, I decided to push myself and try to hit that extra high note. Maybe because I was practicing my lower range or the fact that my voice was maturing, I found myself able to hit the A below middle C with about a 50% chance of it feeling comfortable. So I transposed the song to start on an E with the lowest note as an A. That meant when I sang “free,” I would start at a high E and soar up to an A, a note I knew I could comfortably hit. When I nailed that high note at the next VVDV, some of the volunteers noticed and congratulated me on my efforts. I continued to sing it that way through 2014. After all, once you’re at the top, there’s no going down.

Then I took a long break after. I don’t know whether it was intentional or not, but I didn’t volunteer for the next several years. No one asked me to sing the national anthem. Either they had found someone else or the younger Co-Chairs simply didn’t know I was available. I had graduated from college and was working anyway. I barely had the energy to do laundry when I got home, much less drag myself out to a weekly meeting.

Summer of 2018, they reached out to me about singing the national anthem again. Well, why not? I did it before. I could do it again. So I said yes. In the four years since college, I’d stopped singing regularly. Hopefully with a bit of practice, it would easily come back to me.

Wrong.

My voice had become a rusty pipe. I spent several weeks just getting my voice to feel comfortable singing mid-range songs. To my surprise, my voice had dropped several notes lower, especially early in the mornings before I had a chance to speak a lot during the day. Hitting the A below middle C presented no problems, and I could even hit the G below middle C in my “speaking” voice, something I couldn’t ever manage during high school. For singers who want to hit notes lower than their typical range, they sometimes “speak” it to fake it. Likewise, for singers who want to hit notes higher than their typical range, they sing in falsetto. I’ve never had a need to master falsetto, so I can’t exactly explain how that works, but one example is Coldplay’s Chris Martin whenever he sings in a higher, breathier register.

Over the next month, I struggled to get my voice to reach the higher notes that once came so easily to me. As the big day neared, I finally had to confront the fact that I could only comfortably sing the high F/F#. Attempting to hit either the A or B♭ was out of the question. Maybe if I had accompaniment, the instrumental part could hide my voice straining, but in the dead silence of acappella, you can hear every single wobble. I also hadn’t performed in front of a crowd in four years. Singing for 500 people, including superintendents and senators? I could not take the chance.

The dress rehearsal was my chance to sing in front of a modest crowd of 50 volunteers. This time, I downloaded a piano app so I could play F# right before going up on stage. It was my equivalent of an acappella director’s pitch pipe. While the app worked great at home, I could barely hear anything in the vastness of the ballroom. In the end, I had to do what I always did, and that was to find it relatively by singing a quick test of the first measure. Could I hit that low note? Did it feel too low? Did it feel too high? Okay, it felt right. And then I had to trust that my voice would be able to hit the high note.

It took me awhile before I could summon the courage to start singing at the dress rehearsal. My nerves were wound up tight in a ball, my voice came out wobbly, and my pacing alternated between too fast and too slow. I had to fix this before Sunday. Another thing I’d learned singing acappella was the importance of stage presence.

I know now that I’m not cut out to be a performer either. Back in high school, I still entertained thoughts of becoming the lead singer of a band. Nope, not for me. In my acappella group, I preferred singing as part of the accompaniment, accompanying the soloist with a harmony, arranging music, or designing flyers—literally anything but being the soloist. I make a terrible soloist because I either space out and forget where I am in the song or I’m not very energetic or charismatic in personality.

The U.S. national anthem is the only song that I’ve memorized and always remember no matter how long it’s been since I last sang it. There are a few reasons why I think I’m willing to come back and sing the national anthem time and again. One, I love singing Italian arias. Their graceful melodies are perfect for sopranos, nothing like the low, often repetitive melodies of today’s top 40s. The national anthem is fairly aria-like. Two, it’s a stately song with not many frills. I don’t need to dance around energetically on stage. Did I mention how Dance was one of my two hardest classes in high school? Three, I’ve been singing this song for so long that even if I do space out for a tiny bit, my mind can sort of direct my voice on autopilot.

This time around, I was determined to improve my stage presence during the song. Even though it’s a stately one, I didn’t want to stand there on-stage like a tree devoid of its tree limbs as I’d done in the past. Music, to me, is best enjoyed when you’re naturally moving and grooving to the music. My friends know that at music concerts, I’m the first one out of my chair.

The day arrived. I woke up about two hours before the event to give my voice some time to get acclimated. Singing first thing in the morning is one of the hardest things because the voice hasn’t had time to limber up. After a light, grease- and dairy-free breakfast of a single kiwi, I poured myself a glass of fresh lime juice with a sprinkle of honey and warmed up on the piano. After a couple of run-throughs, it was time to get ready—except for one thing. After the U.S. national anthem, I always end up standing on stage during the Vietnamese anthem, sung in a choir with a guitar, but I never know the words to the song and can’t even satisfactorily lip synch it. It’s rather sad, actually, that even though I’m proud of being Vietnamese-American, I only know the U.S. national anthem by heart and not the classic “Tiếng Gọi Công Dân.” In a panic, I downloaded the lyrics to my phone and hoped I could memorize it when I got to the venue. Perhaps I fattened out because the ao dai’s neckline felt uncomfortably tight and triggered my gag reflex—worst uniform ever for a singer. Plus the traditional hat always felt like it was going to fall off my head if I didn’t balance it right. There was nothing for it. I had to get driving before people started calling me to see if I was on my way.

Once I reached the venue, there were five things I had to worry about. One, I had to keep my voice limber. To do that, I made sure to chat with all of the volunteers. Two, I had to go over the national anthem enough times that I could sing it on autopilot but not too many times that the words turned into meaningless mush in my head. Three, I had to memorize enough of the Vietnamese anthem that I could pretend that I knew it. Four, I’ve never been able to burp as easily as other people, and this is a real problem as a singer. I had to hope I forced a painful burp right before I got up on stage. Five, I needed to stay hydrated enough to “oil” my voice without drinking so much water that my mouth stopped making its own spit and therefore trigger a cough attack.

The moment had come. We lined up beside the stage. We walked up on stage. I stood on the duct tape X. The color guard marched in. One of the color guard members gave a nod of his head. I prayed that all of my preparation would pay off for the next minute and a half. I opened my mouth and sang the first note. As nerves rattled inside me, I tried to imbue some emotion, a head bob here or there (not too much or the hat would fall), and added hand gestures instead of stoically keeping my free hand by my side. I kept my pace deliberate to counteract adrenaline and tried to continually project my voice with force to prevent any wobbliness. I could hear some of the volunteers softly singing along with me. Before I knew it, the song was over. My part was done. I didn’t burp or cough or forget the lyrics or falter at any point. As I stepped back to join the choir, my hurried memorization of the Vietnamese anthem pulled through, and I didn’t feel as glaringly obvious as in previous years. If I ever returned to sing the national anthem, I’d make it my next goal to thoroughly memorize both anthems.

Once I made it to my chair, I gladly stuffed myself with greasy food while listening to the speeches. One of which was U.S. Representative John Culberson’s. An actual Congressman! Political officials rarely made the appearance in person. Usually they sent a representative. Thank goodness my rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner” went relatively well. The first verse lasts less than two minutes, but two minutes can say a lot about an organization or community. Every time I sing at VVDV, I want to represent the Vietnamese-American community in the best light possible, that we respect America and its anthem, and that we’re proud to be here as Americans while building the Vietnamese-American community.

And then I found out why Rep. John Culberson was present.

In mid-June of this year, protests broke out in Vietnam over special economic zones and a new cybersecurity law. Attention over the protests most likely would have slid into the nebula of world news except that something unusual happened—an American present at the protests was detained by the Vietnamese government. And this wasn’t just any American. This was Will Nguyen, a 32-year-old Vietnamese-American from Houston who attended Yale and passionately cared about his studies of Southeast Asia. And he was a VVDV 2004 honoree.

The news exploded on my Facebook feed. Classmates I’d met through Rice University Vietnamese Student Association (Rice VSA) and previous VVDV honorees posted news articles and links to sign a petition demanding Will’s immediate release. It hit even closer to home for me because there are so many similarities between Will Nguyen and my boyfriend, now my fiancé. They’re both young Vietnamese-Americans from Houston who attended Yale and were VVDV honorees. What if my fiancé was the one trapped in the prison of a country halfway across the world? How far would I go to secure his release? Despite being in different cities or attending different colleges, we as Vietnamese-Americans all saw Will Nguyen as someone we knew in our lives, and knowing he was in prison without any contact to friends and family frightened us to the core. Because of that, we instinctively rallied together to protect one of our own in the community.

In mid-July, we anxiously watched and waited for the trial outcome. Would Vietnam prove to be fair and release him or would they truly sentence Will to seven years for disturbing the peace even though he was an American citizen? Would it change how we viewed ourselves as Vietnamese-American, a part of us always drawing back to Vietnam though some of us have never even been to the country and a part of us always struggling to fit the idea of being American? Would it shed a new perspective on our parents’ narratives as immigrants and political refugees? Had we done enough to support one of our own?

They released him. With a huge collective sigh, we celebrated with another round of posts on social media. Will was coming home. There was no telling what he went through during those forty days, but he at least seemed safe and sound physically, unlike the student who died after being detained in North Korea.

A few weeks later at VVDV 2018, Rep. John Culberson recapped the efforts and success of the Vietnamese-American community and government officials in securing Will Nguyen’s release. Will stood and waved when Rep. Culberson acknowledged his presence in the audience. There he was, standing straight and tall in his distinctive black áo dài with floral motifs. The crowd went wild.

As far as keynote speeches go, I rarely remember the contents afterward, even a day later. But for this year’s VVDV keynote speech, Councilmember Dr. Steve Le’s stuck with me because of his three points: 1) hi, 2), one, and 3) remember your roots.

In Dr. Steve Le’s anecdote, he talked about his time as a family medicine resident in a hospital. He always made sure to say hi to everyone, no matter whether they were the CEO or the janitor. Six months later, the janitor retired and invited Dr. Le to his going away party taking place on the topmost floor. Dr. Le had never been on the topmost floor. When he arrived there, he found all the important people at the top—CEO, president, prominent doctors, you name it—present at the janitor’s retirement party. Dr. Le was the only “nobody” there. The lesson here? Always say hi because you never know what doors it could open.

After his residency, Dr. Le moved to a small rural town in Texas called Cleveland to open a practice there. He was initially hesitant at how the people of Cleveland, located not all that far away from the seat of the KKK, would take to having an Asian face serve their community. As he began to employ locals and meet with patients, he always made sure to treat each person as though they were number one, the only one with his attention. Eventually the townspeople came to embrace him and he the people as well, as evidenced by his Texas twang. The lesson here? Treat a person as though they are the only one and you can win their heart.

For the last one, Dr. Le related the story of when his family left Vietnam. They landed at a refugee camp in Pennsylvania, where the summers were moderate and beautiful—but the waitlist to be accepted into the actual city itself, away from the refugee camp, was three months long. His parents, not wanting to wait, asked if there was any other city willing to take them in immediately so that they could start rebuilding their lives. The city? Houston, Texas. So they gave up temperate summers for blistering heat and humidity, not unlike their home country. Yet despite the heat—or perhaps because of it—the Vietnamese community in Houston harbored a blazing passion that left a mark on Dr. Le. No matter how far he traveled for medical school or residency, he kept his Texas Driver’s License knowing that one day, he would return home. And today, in 2018, he was here in Houston, Texas, serving as Councilmember for District F. The family is the most basic unit of a community. Without it, we are nothing. With it, we are stronger. By always coming back to your roots, you can be sure that you’ll never go astray.

And that, I realize, is what VVDV, Vẻ Vang Dân Việt or the Youth Excellence Recognition Luncheon, is really about: taking the time to recognize the achievements of a new generation and the people who made it happen—parents, family, friends, teachers, the community. As many of the speeches noted, “it takes a village to raise a child.” This year, the program added a video montage of each honoree thanking their parents. Some spoke in fluent English, others in fluent Vietnamese. Still others stumbled in Vietnamese or mixed a bit of both into Vietlish. Some of it was funny and relevant. How many of us have never been “the best son” or “the best daughter”? How many of us never did the chores, choosing instead to goof off? Some of it was poignant and heartfelt. How many of us had parents who worked long hours or every single day of the week, month, or year, even, to make sure we had the opportunity to pursue academics and dreams that our parents could never fulfill when they left their home country? How many of us have lost a parent or both or grew up knowing only one? The running joke is that Vietnamese families are notoriously bad at expressing and giving affection. I think it’s much broader than that. All of us, no matter the ethnicity, are bad at taking the time to express and give affection. And who deserves it most but our parents? As each honoree presented a rose to their parents, I found myself tearing up and let the tears run down my face. All around me, others were also moved by the tribute. The Rose Ceremony wasn’t a waste of time at all. It was, perhaps, a rare moment when we actively choose to recognize those who matter the most in our lives while we still have the opportunity to do so.

In Vietnamese, “Vẻ Vang Dân Việt” doesn’t directly translate to “Youth Excellence Recognition,” which always bothered me. I always had a rough impression of what “Vẻ Vang Dân Việt” meant, but it wasn’t until I sat down to write this piece that I tried to nail a more exact translation. On Google Translate, it means “Vietnamese Glory.” According to a Vietnamese-English dictionary, it means “Vietnamese Triumph.” Neither of those really get at what it’s trying to convey. The best I could come up with, with my parents’ help, was “Pride of the Vietnamese People.” This new generation, full of hope for what could be—as U.S. Representative Al Green said in his speech at this year’s VVDV, maybe one day we’ll have a president of Vietnamese descent—this new generation is the Pride of the Vietnamese Community. Though we are a diverse group with different dreams, different beliefs, and different levels of knowledge in Vietnamese culture, we all have something in common. We’re proud to be Vietnamese-American, we’re proud of the achievements all of us have done, and most of all, we’re proud that we accomplished them as Vietnamese-Americans. No matter how far we go in life, no matter what we choose to do in life, we’ll always remember our roots.